The current Disease Outbreak

The current Disease Outbreak News on the multi-country monkeypox outbreak is an update to the previous Disease Outbreak News from 10 June, with updated data, additional information on surveillance and reporting, One Health, gatherings, risk communication, community engagement, and international travel and entry points. We've removed the difference between endemic and non-endemic nations in this issue, reporting on countries as a group where feasible to emphasize the need for a coordinated approach.

As cases of monkeypox spread across multiple locations, scientists have warned that the infectious disease could be transmitted to animals through human medical waste. However, the monkey pox outbreak in predominantly Europe and North America has left scientists baffled as to why the disease has spread so quickly, given that the majority of cases had previously been reported in certain parts of Africa. The president of the World Health Organization for Animal Health has stated that outbreeding could be transmitted to animals through human medical waste. He went on to say that rats can pick up the virus through human medical waste, which, according to specialists, might lead to a global outbreak. Monkeypox was first found in laboratory monkeys in 1958, and since then, numerous animal species like squirrels and rats have been identified as vulnerable to it in areas where it circulates, but the species that are harmed the most in this manner are still unknown.

While epidemiological investigations are ongoing, most reported cases in the recent outbreak have presented through sexual health or other health services in primary or secondary health care facilities, with a history of travel primarily to countries in Europe, and North America, or other countries rather than to countries where the virus was not historically known to be present, and increasingly, recent travel locally or no travel at all.

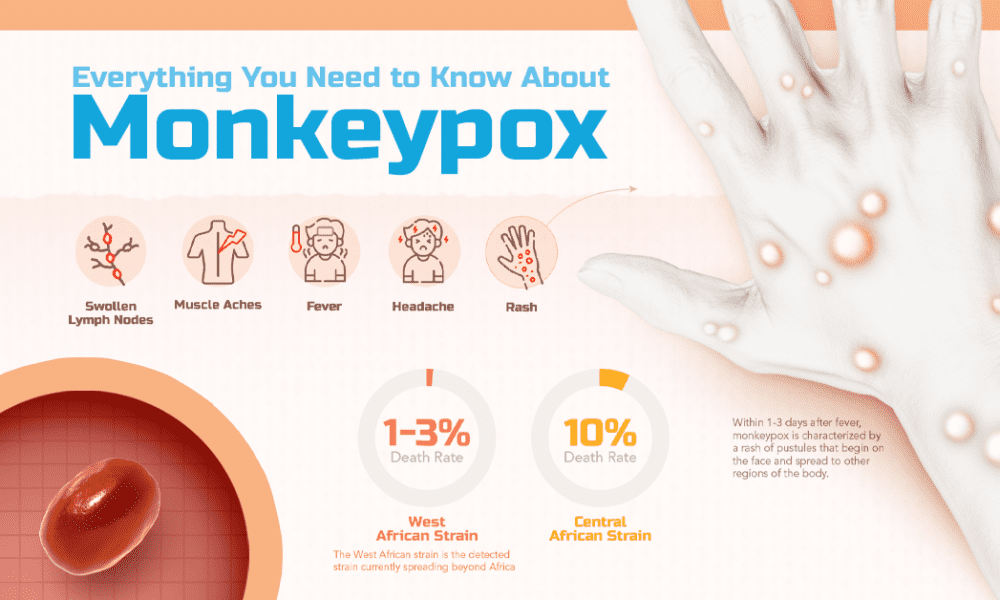

Confirmation of one case of monkeypox, in a country, is considered an outbreak. The unexpected appearance of monkeypox in several regions in the initial absence of epidemiological links to areas that have historically reported monkeypox, suggests that there may have been undetected transmission for some time. According to the World Health Organization, there are presently about 650 confirmed cases of monkeypox infections reported from 26 different countries. The map on your screen displays the nations with the greatest instances, which include areas like the United Kingdom and Spain. Portugal, the Netherlands, and Germany are all members of the European Union. The virus was initially detected in humans in 1970 and has been sporadic in several African countries, including Nigeria, where an epidemic has been continuing since 2017. The clinical presentation of monkeypox patients linked to this epidemic has been inconsistent thus far. Many of the patients in this epidemic are not presenting with the traditional clinical presentation of monkeypox (fever, swollen lymph nodes, followed by a centrifugal evolving rash). The presence of only a few or even a single lesion, lesions that begin in the genital or perineal/perianal area and do not spread further, lesions that appear at different (asynchronous) stages of development, and the appearance of lesions before the onset of fever, malaise, and other constitutional symptoms are all described as atypical features.

Cases have primarily, but not entirely, been confirmed among guys who self-identify as men who have sex with men and participate in broad sexual networks in ostensibly newly impacted nations. Person-to-person transmission continues, with the majority of cases affecting a single demographic and socioeconomic group. It's very possible that the real number of instances is still undercounted. This could be due to a combination of factors, including a lack of early clinical recognition of an infectious disease previously thought to be limited to West and Central Africa, a non-severe clinical presentation in the majority of cases, limited surveillance, and a lack of widely available diagnostics. While attempts are being made to close these gaps, it is critical to keep an eye out for monkeypox in all demographic groups in order to avoid further transmission. Transmission is currently predominantly tied to recent sexual interactions in nations that appear to be recently impacted.

There's a good chance that more instances may be discovered without identifiable transmission pathways, possibly in different population groupings. Given the large number of nations reporting cases of monkeypox across various WHO regions, it is quite possible that more countries will discover cases and the virus will spread further. Close or direct physical contact (face-to-face, skin-to-skin, mouth-to-mouth, mouth-to-skin) with infected sores or mucocutaneous ulcers, particularly during sexual activity, and respiratory droplets. All patients discovered in newly impacted countries with PCR-confirmed samples have been identified as West African clade infected. Monkeypox virus is divided into two clades, one of which was initially discovered in West Africa (WA) and the other in the Congo Basin (CB). The WA clade has previously been linked to a case fatality ratio (CFR) of less than 1%, but the CB clade appears to produce more severe illness, with a CFR of up to 10% previously recorded; both estimations are based on infections among a mainly younger population in the African environment.

Patients with a rash that progresses in sequential stages – macules, papules, vesicles, pustules, scabs, at the same stage of development over all affected areas of the body – may be associated with fever, enlarged lymph nodes, back pain, and muscle aches should be on the lookout in all countries. Many people are experiencing uncommon symptoms during this epidemic, such as a localized rash with only one lesion. Lesions may arise asynchronously, with a predominantly or entirely peri-genital and/or peri-anal distribution, as well as localized, painful swollen lymph nodes. Some individuals may have sexually transmitted infections, which should be checked for and treated as needed. These people may show up in a variety of community and health-care settings, including primary and secondary care, fever clinics, sexual health services, infectious disease units, obstetrics and gynecology, emergency departments, and dermatological clinics, to name a few. Passengers and anyone who may have had close contact with an infected individual while traveling should be contacted by public health officials in collaboration with travel operators and public health equivalents in other places. At points of entry, health promotion and risk communication materials should be available, including information on how to recognize signs and symptoms that are consistent with monkeypox, the precautionary measures recommended for preventing the spread of the disease, and how to seek medical care at the destination if necessary.

WHO urges all Member States, health authorities at all levels, doctors, health and social sector partners, and academic, research, and commercial partners to act immediately to stop the spread of monkeypox locally and, by extension, globally. Before the virus may establish itself as a human disease capable of efficient person-to-person transmission in previously or newly impacted areas, swift intervention is required.

No comments:

Post a Comment